Written in the 1780s, it both enlightens and confounds. Its brilliance is undiminished, but the intervening years make it feel distant, at times impossibly so, challenging modern interpreters to understand what an 18th-century text means today.

Sadly, our attempt to understand the U.S. Constitution has too often become a mechanistic search for a correct answer, with little nuanced judgment. That is thanks to the ascendance of originalism on the Supreme Court. The originalist justices believe the meaning of the document was fixed when it was enacted, as opposed to living constitutionalists, who argue that the meaning and application of the Constitution should adapt to a changing world and not be bound by the judgments of men who lived centuries ago.

The originalist methodology fails to acknowledge the role that one’s individual judgment inevitably plays in interpretation. Total objectivity is an attractive but dangerous illusion that shields the court from wrestling with our society’s complexity and from criticism of its opinions.

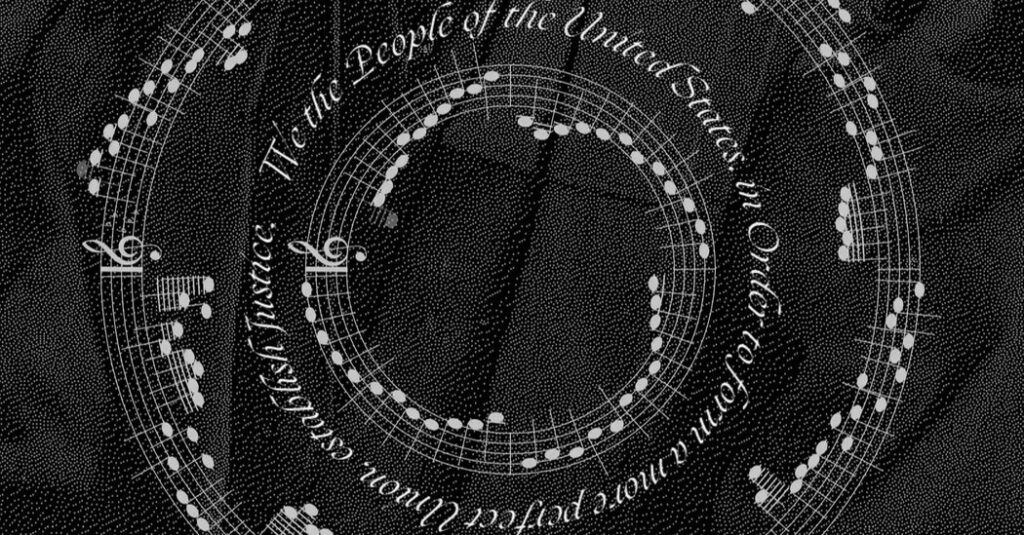

Today, with a confrontation between the executive and judicial branches seemingly underway, the need for a thoughtful, credible reckoning with the Constitution’s meaning is especially urgent. Legal scholars, judges and constitutional lawyers would do well to consider the way interpreters have wrestled with different but equally challenging late 18th-century texts: classical music compositions.

Art and the law, of course, serve vastly different functions in society. But the performing musician’s embrace of complexity is precisely what is needed from the courts at this moment.

To a musician, a strictly originalist approach feels intolerably constricting, even perverse. A compelling performance of a piece of music requires both accuracy and creativity, insight and instinct, reverence for the composer and the breath of life brought by the interpreter.

Accuracy, while essential, is a slippery goal. As is true in the Constitution, the information in a musical score is necessarily incomplete and indistinct. Musical notation, however extensive, can never convey all of a piece’s nuance and emotional content. It provides clues about the composer’s intent, not definitive answers. It is not alive on the page; it is a performer’s reckoning with it that makes it flesh and blood.

In his final sonata, Beethoven asks the pianist to build to the peak of a crescendo on one very long note: a physical impossibility on a keyboard, whose sound begins to decay the moment the note is struck. This crescendo is not a simple request for the pianist to get louder. It is Beethoven’s way of conveying that this passage should evoke a feeling that might typically involve getting louder. Or maybe it is Beethoven’s way of conveying that this passage should evoke the feeling of attempting the impossible.

Schubert’s E-flat Major Piano Trio contains over a thousand accents. A strict textualist approach would mean playing the accented notes louder than their neighbors with numbing regularity. What is really required is an examination of the myriad reasons — insistence, yearning, anxiety, for starters — that Schubert might want them emphasized.

It may be comforting to take something immensely complicated, for example, Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 21 in C Major, K. 467 — an encyclopedia of human feeling conveyed with terrific psychological acuity, written in 1785 — and make it simple. But this is not interpretation. Declining to engage with the complexity and ambiguity in Mozart means missing his greatness altogether, just as interpreting “the right to keep and bear arms” or “due process of law” as simple phrases with a meaning locked into place in 1791 misses their subtlety and utility to our modern world.

So, in the case of music, what is interpretation? What makes a reading vibrant, alive and persuasive?

It begins with instinct. If Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 21 does not set your pulse racing and inspire feelings that you cannot name, you have no foundation for grappling with it, and no good reason to do so.

Then comes the work. You gather information. You learn about form — the way pieces of music were constructed in the 1780s, and by extension, the ways in which the piece at hand fulfills and subverts expectations. You learn about the conventions of the time, which led Mozart to notate in ways that can be counterintuitive to modern eyes and ears. And yes: You treat the marks on the page with extreme seriousness, which means asking yourself why the composer placed them there. Why a slur connecting notes begins in one place and not another; why a phrase, on its second appearance, has changed from piano to forte, or from dolce to cantabile.

But you don’t pretend that your interpretive choices, forged through years of study and trial and error, are separable from your humanity. Your understanding of the music is alive and fleeting and will continue to evolve as you mature and the world changes around you. And the same is true for your listener: Mozart sounds different to people who have heard Schoenberg and The Grateful Dead than it must have to its original audience. The interpreter must reckon with our changed sonic landscape in deciding how best to convey a phrase’s meaning.

This does not make the enterprise hopelessly subjective. Interpretation — of Mozart or the Constitution — is neither mechanical reproduction nor unfettered creativity. It is about using your eyes and ears and lived experience and education and critical lens and passion and skepticism and, above all, humility, to tease out the text’s infinite implications, and in doing so, to come closer to its essence.

Speaking about Mozart’s K. 467 concerto, the great pianist Leon Fleisher once said, “It can never be beautiful enough; it will always be more perfect in the imagination.” A performance of a work by Mozart, like our union, will never be perfect. But a life devoted to making either more perfect is a life well spent. It is a process requiring honesty and modesty, an ongoing, restless quest for an understanding that acknowledges the ambiguities inherent in a great text. With that devotion, these documents shape and reshape our consciousness; without it, they are mere paper.